Jill Rajewicz currently works as a Physical Scientist for the Canadian Ice Service in Ottawa. Passionate about polar research, she sits on the board Association of Polar Early Career Scientists (APECS) Canada chapter. In her free time, she loves to cross-country ski, mountain bike, and read.

I decided to study science because I have a deep interest in the natural world. Time spent outside exploring the wilderness as a child and adult made me yearn for a better understanding of the landscapes I loved; I wanted to know why things looked like they did and what processes were at work. This eventually led me to the field of Geography. Physical Geography is all about studying the processes operating at the surface of the Earth and in the atmosphere; geographers want to know how the atmosphere, the lithosphere, the biosphere, and the hydrosphere interact to shape the world and produce the spatial characteristics we observe. My classes in hydrology, meteorology, permafrost studies, geomorphology, and climate change (to name a few) gave me the tools to answer the questions I had about natural phenomena I was interested in, and equipped me to look at the world with a holistic, big-picture lens to tackle complicated environmental problems. I take delight every day in having a deeper relationship with the natural world because of my training in science.

I have a particular interest in glaciology (the scientific study of glaciers, and ice more generally) and the polar regions. After completing my undergraduate degree, I moved to Ottawa to complete my Master of Science with Dr. Derek Mueller in the Water and Ice Research Lab at Carleton University. I examined how freshwater from terrestrial ice and snow melt drains beneath an ice shelf (a huge platform of ice that floats on the ocean but is attached to land) in Milne Fiord, on the northern coast of Ellesmere Island. To do this, I mapped ice thicknesses using ground-penetrating radar, and studied the properties of the near-surface water column in the ocean beneath the ice shelf. I found that the (relatively) warm freshwater has incised a deep channel upward into the base of the ice base, creating an ‘upside down river’. Channelization, and thinning of the ice shelf along such a channel, weakens an ice shelf and makes it more vulnerable to fracture. Canadian ice shelves are rapidly breaking up; my research suggested that channelized drainage could be an important mechanism driving ice shelf loss.

Taking a profile of water salinity and temperature with depth through a hole in the sea ice on the Arctic Ocean as part of my NSERC-funded master’s research examining freshwater drainage beneath the Milne Ice Shelf.

One of things I love best about being a scientist and geographer is doing field research. I have been lucky to do lots of fieldwork already in my scientific career – I’ve mapped Whitebark Pine in the Canadian Rockies, sailed through the Northwest Passage on scientific research cruises aboard the CCGS Amundsen, and collected glaciological and meteorological data on southern Ellesmere Island as an undergrad. For my MSc. in Geography at Carleton University, I spent three summers working at my field site on Northern Ellesmere Island.

Here I am conducting a survey of ice thickness on the Milne Glacier using a geophysical method called ground (ice, in this case) penetrating radar. It sends a pulse of energy into the ice; this energy is reflected back to the surface when it hits the boundary between the ice and the rock or water that lies beneath. Based on the travel time of the reflection, and knowing the velocity of a radar wave in ice, we can determine ice thickness.

Spending time observing the environment is so important in stimulating new questions and insights, and having data gathered in-situ is invaluable for the processes and systems I study. However, the fact that you are dealing with an unpredictable environment can also make it very frustrating and hard. Things go “wrong” all the time in fieldwork! Sometimes it’s the weather, sometimes your instruments don’t work as expected, sometimes you realize you left that extremely crucial piece of equipment 3000 km away back in the lab... Often, it’s just that the real world is unpredictable and changeable, and the perfect plan you devised at your comfortable desk just doesn’t work in practice. I found it incredibly stressful to have to suddenly adapt my plans or improvise when I first started doing fieldwork. I was afraid to screw up and do something the wrong way, so much so that I often didn’t ask questions or seek guidance when I should have. Many seasons of fieldwork have taught me that mistakes (in fieldwork, but in doing science in general!) are inevitable, and are part of the learning process that ultimately make you a better scientist. It’s okay not to know everything or to admit you have made an error. Your supervisors/bosses will understand – they too were beginning scientists once! The important thing is to be resilient in the face of setbacks and not give up when you are challenged. Fieldwork teaches you to be good at being flexible and thinking on your feet. Now, I enjoy the challenge of quickly coming up with plans B through Z after plan A fails, and I find it fun to have to be creative and look at problems from unexpected angles. These are all skills that have served me well in other areas of my scientific work as well.

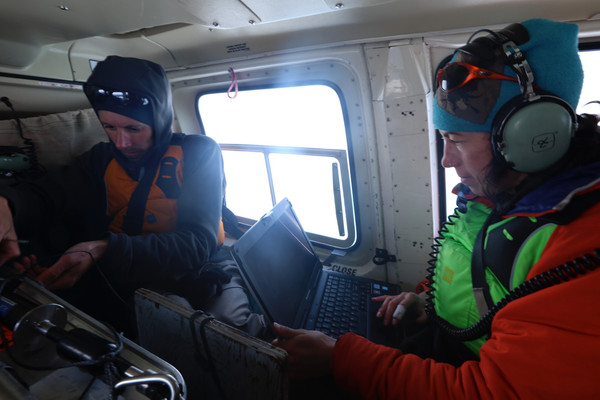

When you are doing fieldwork, your office can be anywhere! Here, we are programming instruments as we catch a ride in a helicopter to our next sampling site on the Milne Ice Shelf.

Though there are definitely challenges, fieldwork is also fun, exciting, and inspiring. I love to be outdoors, camping and hiking and skiing for work. Being immersed in the world and observing processes and patterns with your own eyes encourages curiosity and spurs you to ask new questions and devise new ways to investigate problems. I have been fortunate to see places in the High Arctic that very few other people will have the chance to visit. Working and living in close quarters with other scientists in sometimes challenging conditions allows you to build unique relationships. You learn to be a good member of a team and a good communicator. Beyond just hard science skills, I have learned skills like how to run a camp completely on solar power, and how to exit a hovering helicopter. Meals taste extra amazing when you have been working hard outside all day, and the pleasure of the first shower after a month in a remote field camp cannot even be described! Thoughts of fieldwork to come (or good memories of being out there) are very motivating when you feel stuck on writing or statistical analysis.

Home sweet home at the Milne Glacier camp in Milne Fiord, northern Ellesmere Island. At 82 degrees North latitude, the sun doesn’t set in the summer - this picture was taken at 1 am!

In the summer, temperatures in the high Arctic can be warm and pleasant. Here is my team and I eating dinner and relaxing in the most beautiful dining room in the world, on Ellesmere Island.

I hope there is much more field research to come in my career as a scientist. I encourage anyone interested to take opportunities to participate field research as it is a whole new dimension to studying the natural world. My experiences in field research inspire this advice to women and girls considering a career in STEM: If you are curious and passionate, you can learn the skills you need to work in STEM even if it doesn’t feel like it comes easily at first – this is normal! Learning to think scientifically often comes with a lot of mistakes but these challenges are all part of practicing and improving your skills as a scientist. Creating new knowledge and making discoveries is hard work but it is so worth it.

Field research is hard work and for me, often involves long days, carrying big loads, and travelling long distances on foot. Nowhere better for a nap for a glaciologist than next to a glacier!